In 2021, Americans spent $4.3 trillion on healthcare services.

Despite spending nearly $13,000 per citizen, the U.S. healthcare system still ranks last on key healthcare outcomes — access to care, administrative efficiency, and equity — when compared to other wealthy nations.

No one solution can reform our complex healthcare system. However, we believe interoperability and unlocking the value of all healthcare data will be key drivers of better care.

To explain why, let’s first explore how the U.S. healthcare system reached its current crisis point.

The inertia of healthcare

A complex network of caregivers, indirect facilitators, and intermediaries fills our healthcare system with inertia against systemic changes.

Consider Sam, a teacher from Texas in her early forties. She’s been feeling drowsy and experiencing frequent urination, so she decides to consult her primary care physician. Sam sets up an appointment and has some blood work done. During her outpatient visit, Sam is diagnosed with diabetes. She’s prescribed Metformin and advised to make dietary and lifestyle changes. The receptionist collects her insurance, and she’s assisted by a nurse to order her meds.

In a single visit, Sam interacts with the physician, lab technician, receptionist, and nurse. She also indirectly interacts with insurance, payment processing, pharmaceutical companies, and intermediaries like an electronic medical record (EMR) vendor and pharmacy benefit manager (PBM).

Any change made to the healthcare system directly or indirectly affects all of these stakeholders. Well-meaning interventions need to contend with existing priorities, competing interests, and familiarity with existing protocols.

Sam lacks control or insight into the decisions being made. Her employer chooses the health insurance plan and provider, her physician chooses the EMR platform, regulations provide guidelines, and EMRs implement data-sharing controls. Often, healthcare operators, have their hands tied too. Healthcare has high switching costs, so even if physicians aren’t happy with their EMR or patients aren’t entirely satisfied with an insurance plan, they tend to stick with what they’ve got.

All of these factors add layers of institutional inertia that make the U.S. healthcare system resistant to change, even when frustrations and inefficiencies are clear.

How did we get here?

HITECH and the digitization of healthcare

The modern era of healthcare was kicked off by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, which was signed into law in 2009.

HITECH’s goal was to improve healthcare quality and efficiency and reduce costs by promoting the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology. It rapidly accelerated the digitization of healthcare through financial incentives and penalties, especially record-keeping and payments. Studies have shown that HITECH led to positive outcomes, such as reducing preventable adverse drug events (ADE).

Notable achievements:

HITECH strengthened civil and criminal enforcement of the HIPAA security and privacy rule.

It made interoperable EHR adoption a critical national goal and invested >$35B into subsidizing EHRs for hospitals and ambulatory care.

It provided additional incentives for hospital systems to use electronic health record systems (for example, payments to those using certified EHRs and penalties as a percentage of Medicare payouts if you don’t adopt an EHR).

It required doctors to show “meaningful use” of an EHR system — which led to the rise of Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) to move data between systems as demonstrations of basic interoperability

But HITECH also had unintended consequences.

For one, administrative burden, particularly data-entry work, skyrocketed. Have you ever wondered why your physician spends so much time per visit entering basic information into a computer or tablet? HITECH mandated that all stakeholders who directly interact with patients have to manually enter health data into digital record systems, but did not consider the additional burden this would place on care providers.

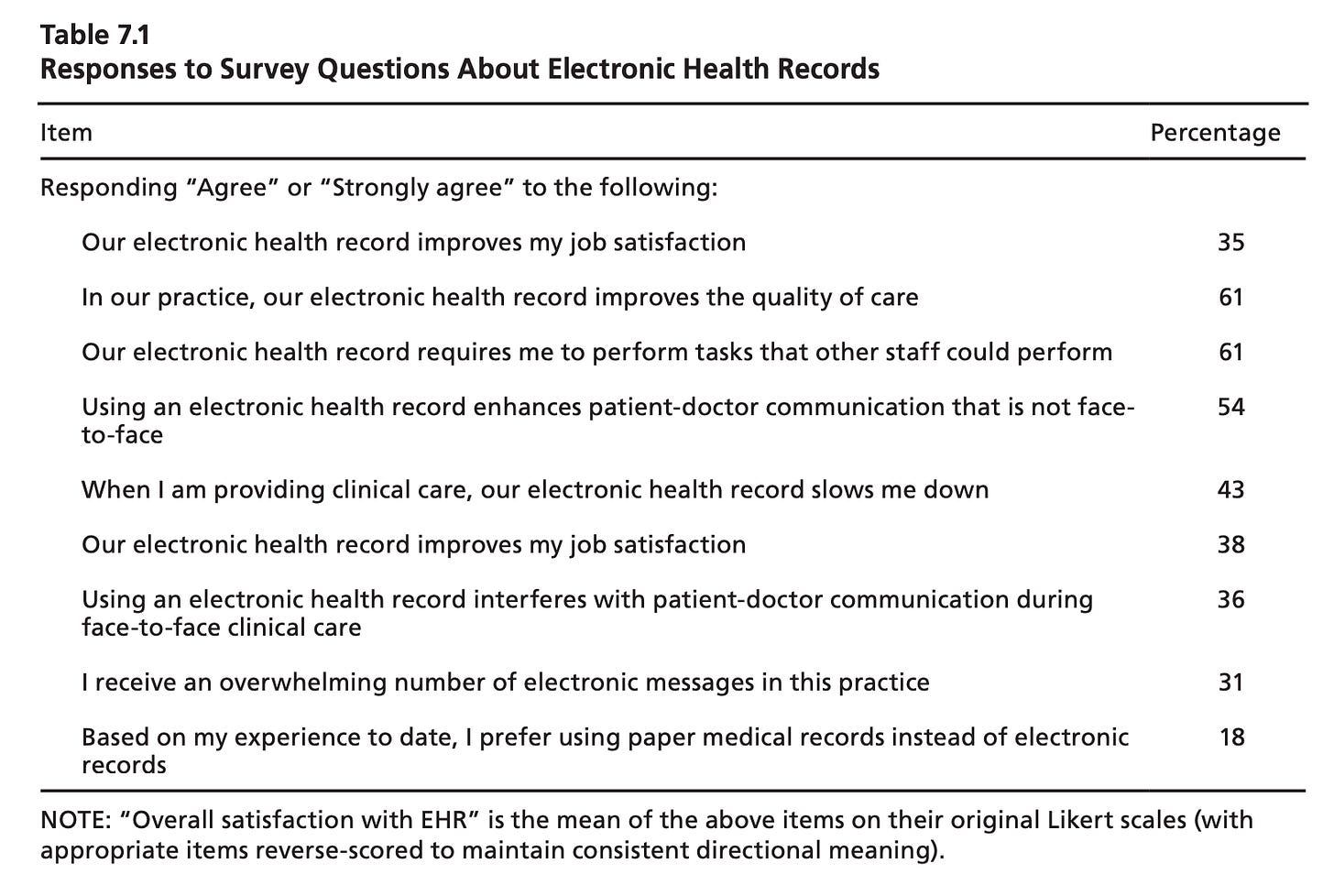

Many physicians view EMRs as a driver of dissatisfaction rather than a net benefit (you try clicking through an EMR over 50 times just to enter patient info, for every patient, day-in and day-out, and stay upbeat).

A flaw in HITECH was that it explicitly defined processes like entering data into EMR systems, but overlooked incentivizing the outcomes those processes were supposed to lead to, like improving care delivery or meeting the needs of care teams.

We’ll get more in-depth on HITECH, and what we think future legislation can do better, in a future post.

The EMR is for more than just billing

The next major piece of healthcare legislation was the 21st Century Cures Act (21CCA), which was passed in 2016 in the twilight of the Obama administration.

21CCA’s goal was to make developing and approving new medical products more efficient. It gave the FDA new authority. For example, the FDA would allow the use of “real-world data” — data related to patient health status and/or the delivery of care, including data from EMRs — in supporting the approval of new drugs and expanding access to existing ones.

In 2018, the FDA defined a framework for companies to provide "real-world evidence" to support the approval of new therapies and devices, including observational studies, insurance claims data, patient input, and even anecdotal data.

These rules meant that EHR and third-party health data became more valuable, and grew the real-world data market by billions of dollars.

We experienced RWD’s skyrocketing rise firsthand at Foundation Medicine — in 2017, we were part of a team that had developed a comprehensive, anonymized real-world dataset. In this dataset were oncology patients’ comprehensive genomic profiles from Foundation Medicine and their longitudinal clinical data and outcomes from Flatiron Health’s EMR. With these data, we could replicate previous clinical findings for a fraction of the cost and time, and make discoveries, such as how emerging immunotherapies were benefiting specific patient populations.

In 2018, Roche acquired both Foundation Medicine and Flatiron Health for over $4B in additional capital.

Interoperability becomes a critical need and focus

21CCA also defined “interoperability” between healthcare systems — “all electronically accessible health information” needs to be accessible and usable “without special effort on the part of the user.”

Critically, it prohibited institutional players from information blocking, or blocking access to medical history or treatment information. As with HITECH, financial incentives were significant; Blocking carries fines of up to $1M per violation.

And it established the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) — which provided nationwide governance for the exchange of health information, to support data sharing across health networks.

Ten years ago, accessing electronic medical records was incredibly challenging. Today, leading EMR integration providers like Redox enable developers to build new innovative data products by streamlining access to structured data variables, like patient demographics, codes, and certain lab results.

Regulatory forces continue to drive data standardization & interoperability

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) continues to expand requirements for healthcare data interoperability.

The ONC, in its 2022 report to Congress, acknowledged that “Among hospitals, for example, the most cited barriers to sending and receiving information do not relate to the hospital’s IT but rather to their partners’ IT….”

They conclude that establishing technical standards and aligning stakeholders will support “information sharing … using APIs and USCDI.”

In 2022 alone, the ONC:

Announced details for “Project US@” Tech Spec — a unified, cross-standard approach to connect healthcare organizations and improve patient matching, or identifying a patient across healthcare systems. Bad patient matching hinders patient care and can even lead to harm. The PU@ workgroup included the CDC, EHR vendors, HL7, the National Council for Prescription Drug Programs, X12, and others.

Released the US Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI) spec 3 [PDF], a standardized set of health data elements for nationwide HIE & interoperability.

Signaled that unstructured data will become a larger focus for them in the future. They began by standardizing the kinds of unstructured notes used in HIEs and will turn their attention to standardizing content in the next 5 years. They also doubled down on LOINC, SNOMED, ICD-10, CPT, and HCPCS as supported ontologies.

Threw more weight behind FHIR, the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource, an API-focused standard for health information representation and exchange. FHIR is maintained by Health Level 7 (HL7), a standards development organization. By December 31, 2022, all certified technology developers across their entire customer base were required to deploy a standard FHIR API. Their hope is to create a climate for innovation as apps can now be developed that will work across all certified electronic health systems.

We are building towards a more online, consumer-driven healthcare system — much faster than anyone expected.

COVID-19 has permanently elevated consumers’ expectations

Since the pandemic, we’ve seen a major transformation in how care is delivered and managed.

Before 2020, telemedicine was considered by many to be a “nice-to-have” or even a fad — until it became pivotal to basic care.

According to a 2021 McKinsey report, claims for telemedicine use during outpatient care and routine visits grew by ~7800% between February and April 2020. Telemedicine use dropped after the first wave but stabilized at around 3800% growth, comparing February 2020 to 2021.

Dealing with COVID-19 seems to have permanently elevated consumers’ expectations of how they can receive care. For one, we’ve seen sustained adoption of cloud-native, consumer-friendly healthcare platforms and services. One staggering statistic that a health exchange expert recently shared with us: the volume of healthcare data on digital platforms will eclipse data added to EMRs within two years.

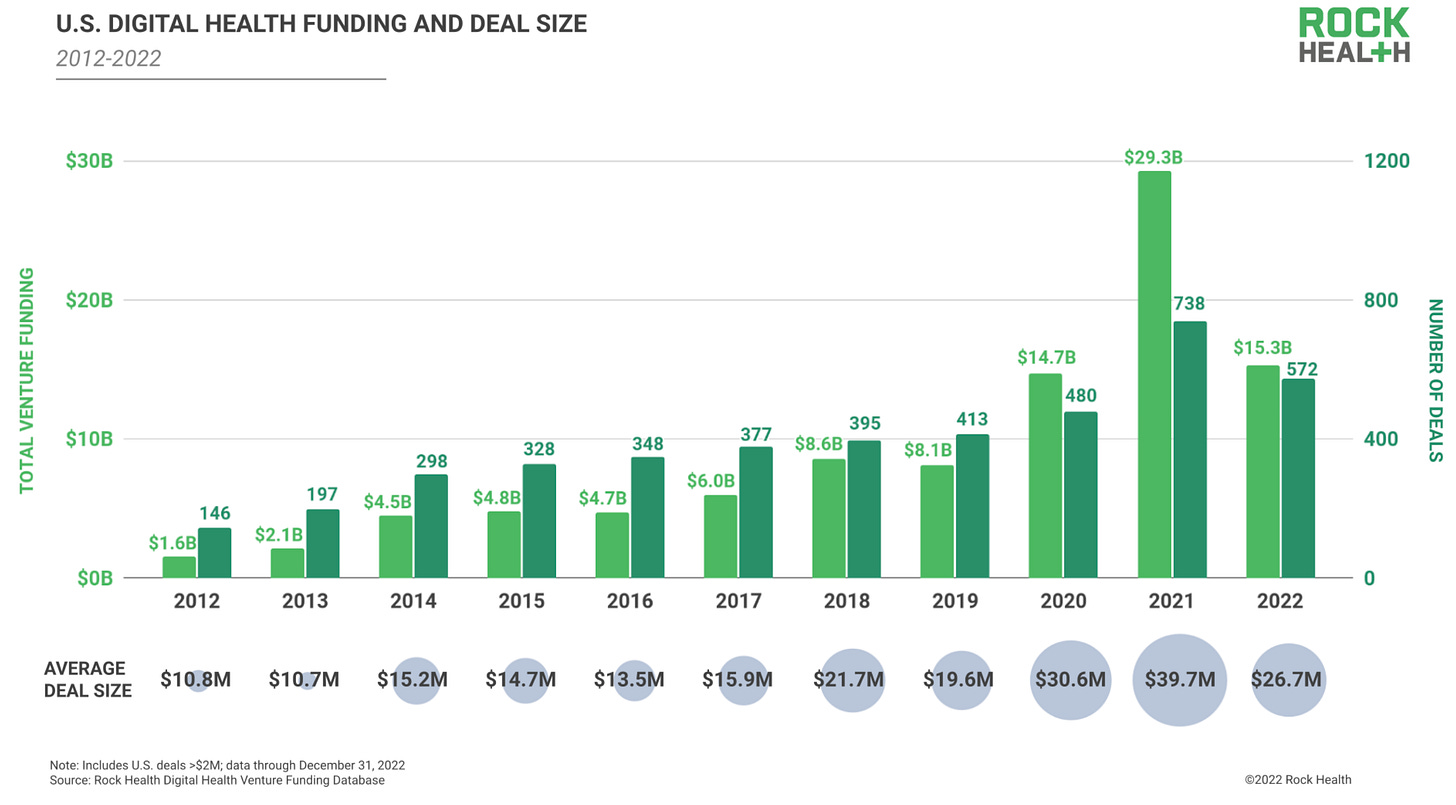

At the same time, total venture funding for digital health grew from $8.1B in 2019 to $15.3B in 2022 (as with telemedicine use, we saw a spike in investments during the early pandemic, followed by attenuation but an overall net increase).

Upwards trends in digital health funding and telemedicine use align with the ONC’s aspirations to make healthcare solutions as easy to access as financial or consumer services.

In sum, we are building towards a more online, consumer-driven healthcare system — much faster than anyone expected.

The next frontier in healthcare

A more consumer-friendly healthcare system will need to learn from its data.

Yet there is still work to be done. The ONC recognizes that major blockers remain to the private and secure exchange of structured healthcare information.

Moreover, the most insightful data is also the hardest to use: intake notes, diagnostics reports, remote voice or video consultation transcripts, pathology reports, and more. These unstructured data are not easy to organize, search, or analyze — even though they provide crucial context for understanding a patient’s past, present, and possible futures.

If we could properly use the unstructured universe of healthcare data at scale, it could help us understand patients far beyond what’s easily accessible in the EMR. And ultimately, we hope, enable a more equitable and patient-centric healthcare system.

So how do we do it?

In future posts, we’ll explore how an explosion in artificial intelligence will drive the next digital revolution in medicine.

Thanks for reading,

Gaurav & Will

A huge thank you to Alda Cami for providing feedback on this post.

Very insightful article. When you consider AI in the next post, I hope you'll also look at the oft-neglected richness of data that can exist in the DICOM realm ; not just for radiology but also potentially ECG and visible light modalities too.

Great post, excited to read more about how AI will impact healthcare.